Keywords

Physics, Astrophysics, Astronomy, Planets, Exoplanets, Deep Space, Space Telescopes

Introduction

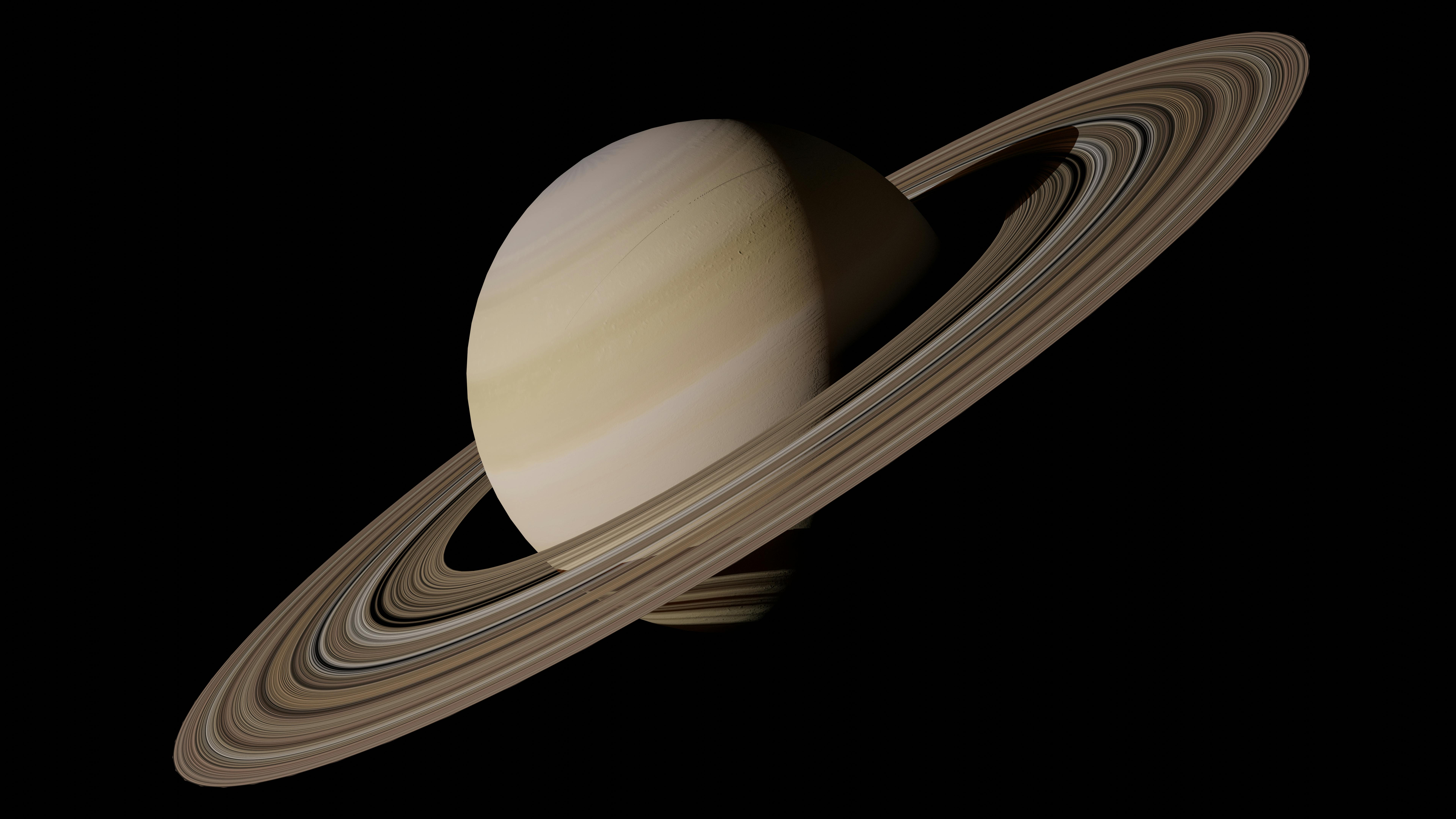

Of all the wonders that can be observed within our solar system, there are few that are more iconic than the rings of Saturn. As a result of their outstanding beauty, scientists for centuries have been drawn to Saturn’s ring system, studying this system extensively. This knowledge of planetary rings and the mechanics behind them now serves an important purpose. As we, the human race, begin to look further out into the cosmos, we can put to use the lessons learnt from our stellar neighborhood to identify objects further out in space.

Saturn’s Ring System

From observations alone, you would be forgiven for thinking that Saturn’s rings are solid objects which orbit the planet. However, upon closer inspection, it is revealed that the structure of the planetary rings consist of millions and millions of tiny ‘dust’ like particles. These particles vary quite significantly in size, from being just a few microns in diameter to over 30 meters wide.

Another feature of interest when considering Saturn’s rings, would be the presence of gaps within the rings such as, the Cassini division. Since, we know that the ring structure is made up of millions of particles, why do gaps exist within the ring system, and what causes them to form?

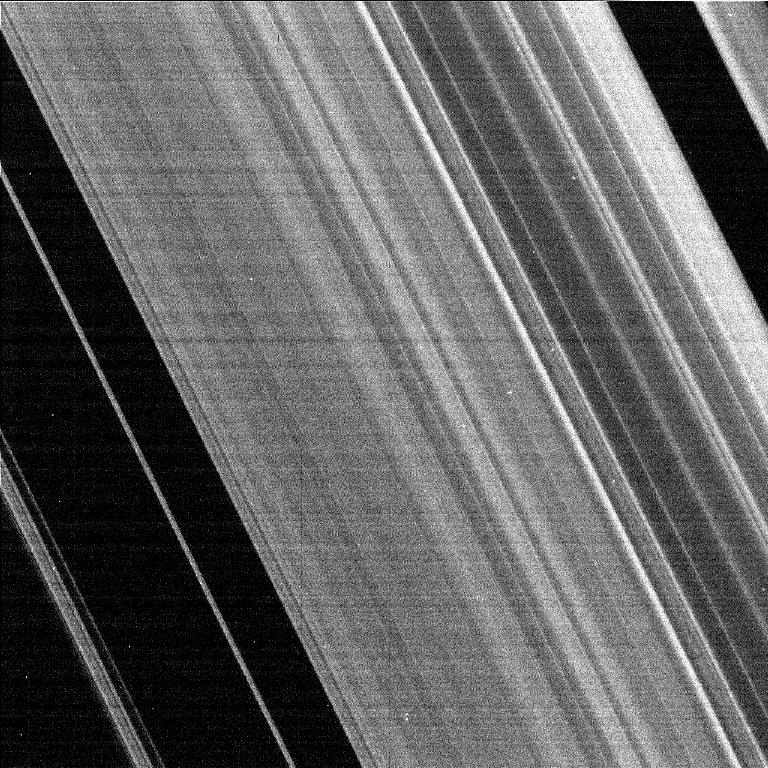

At present, there are two known mechanisms responsible for the formation of gaps within planetary rings. The first of which is known as embedded moons. These are similar to traditional moons that would be found orbiting a planet however, these are found to be orbiting within the ring system itself. As a result of the moon being physically located within the ring system, a gap is cleared within the system where the embedded moon is gravitationally dominant. The gap that has now been created by this moon will now be maintained for as long as the moon exists, furthermore, the width of the gap actually relates to the mass and therefore the size of the moon.

The second mechanism is a touch more complicated; this gap formation method occurs due to orbital resonance. Orbital resonance occurs when two or more orbiting objects have orbital periods (the time taken to complete one full orbit) that can be related by a ratio of small integers (e.g. 3:1). As a result of this relationship between orbital periods, the two bodies exert a regular, periodic gravitational influence on one another.

Consider a moon orbiting outside of a ring system and a particle within the ring system. The particle in the ring system might orbit the planet twice for each orbit of the moon. These two objects are considered to be in an orbital resonance. At each point the orbits align the moon and the particle exert a gravitational ‘tug’ on each other, over time the so called gravitational ‘tug’ can build up to have significant impact.

When the particles within the ring system are found to be in orbital resonance with a moon outside of the ring, the gravitation influence of the moon is found to change the orbit of the particle in the ring. As a result, there is a region created within the ring system that is cleared of particles simply due to the influence of a moon located outside of the ring system. Since, Saturn has lots of moons, there are also lots of gaps within the ring system that oftentimes relate to the presence of a moon.

Understanding the Strange Case of J1407B

So how does this information help the modern astronomer, looking out deeper into space? As astronomy continues to evolve as a discipline the way we use telescopes is changing, among others, a new role for telescopes now exists, survey telescopes. Survey telescopes are designed to map an entire area of the sky, quickly and efficiently, collecting lots of data that can then be studied by scientist at a later date. In particular, telescopes like the Kepler telescope and the TESS telescope are designed to survey the light coming from stars.

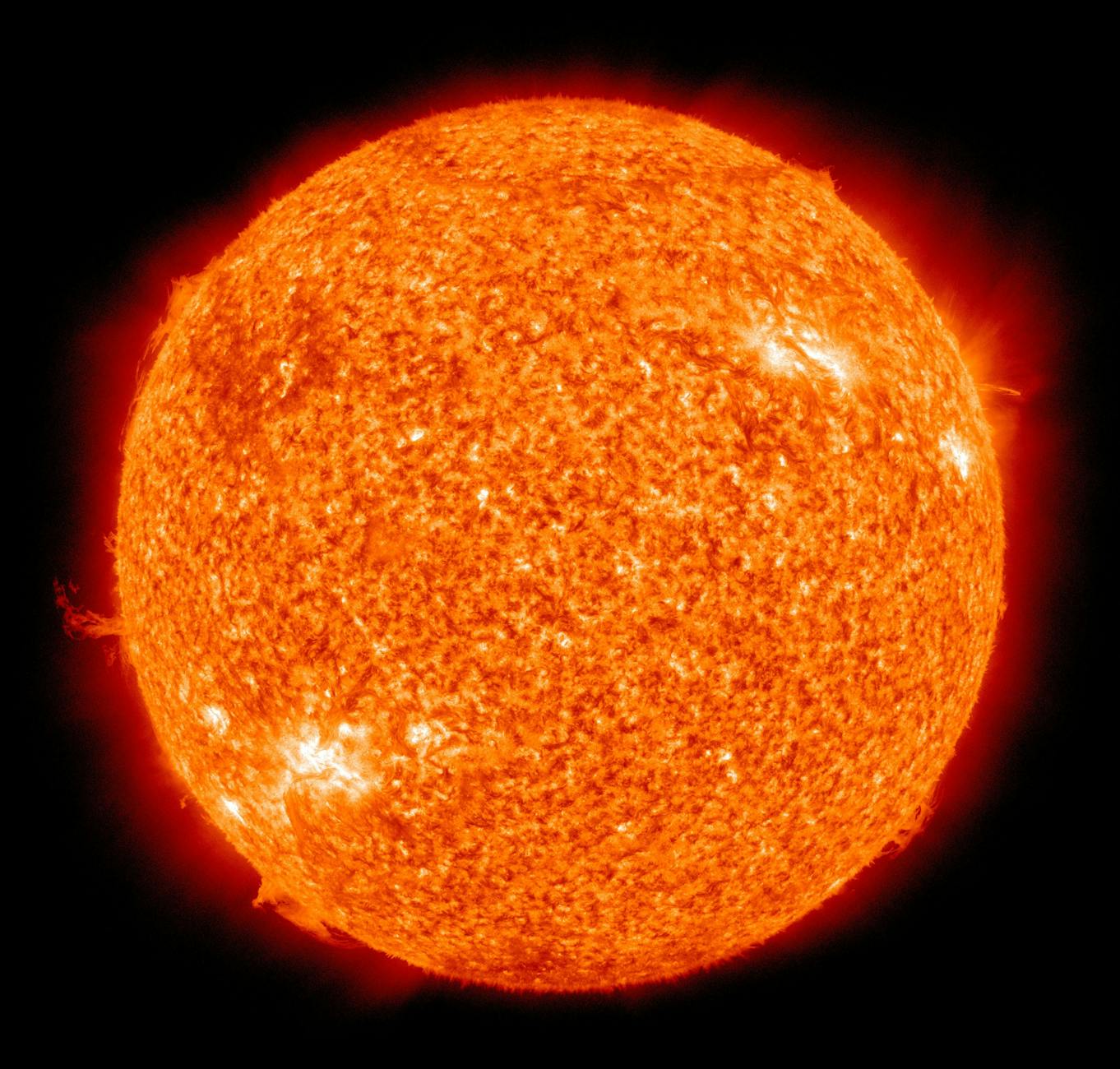

With proper analysis, the light of a distant star can reveal all kinds of information about the star such as, the mass of the star, the diameter of the star, and even about any objects that might be orbiting a star. An example of this would be what astronomers call the Transit method, used to identify exoplanets.

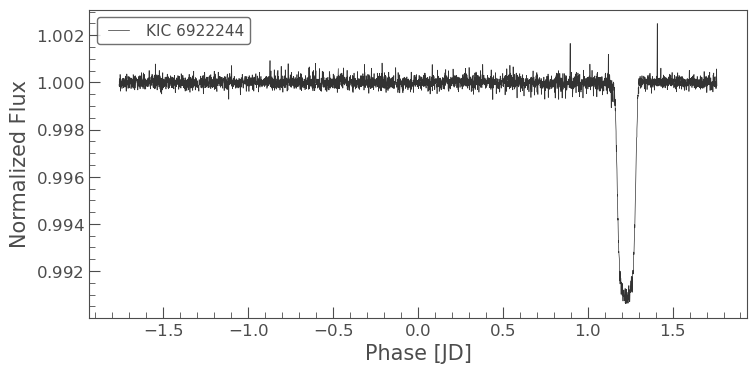

The transit method is a simple analysis of the light of stars. When a celestial object such as a planet passes between the star and the Earth, from the Earth we observe a significant dip in light intensity. From the duration of the dip and the amount of light that is restricted, an astronomer can discover important details about the nature of the object.

In one particular case, when examining the light curve for a star named V1400 Centauri (Catchy, I know) some very unusual features were noticed. First of all, the period of transit was extremely long, the transit lasted for more than 56 days, which is way to long for a planet to be orbiting the star. Secondly, the distinctive u-shaped dip of the transit, was not present, instead the light curve was chaotic.

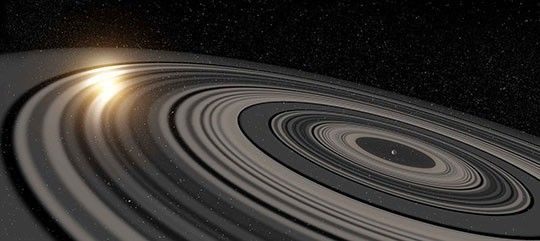

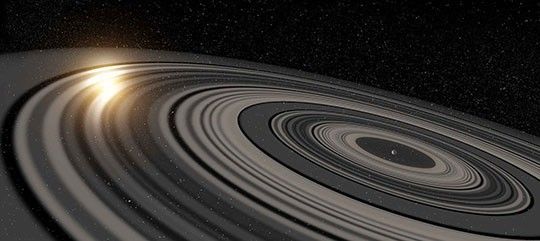

The object, designated J1407b initially stumped scientist and posed somewhat of a question mark. However, scientists were able to figure out, from studying Saturn’s rings, that this object was in fact a massive ring system. There remains some margin for error, as we cannot directly observe this object, but it is generally accepted that J1407b is a circumplanetary disk, or in other words a massive cloud of dust and gas that will one day may form into moons, exomoons and satellites.

The chaotic structure of the light curve stems from the design of the ring system, and scientists have been applying what we know about the formation of Saturn’s rings to attempt to figure out how this giant ring system came to be. This is important area of research, as this is a window into the very beginnings of a new stellar system, with potential to learn about the mechanisms that underlie star formation as well as planet formation, areas of astrophysics that are at present not completely understood.

Conclusion

This specific case is just one example of how the lessons we have learnt, studying our own galactic neighborhood, can help to develop our understanding of objects that are found within deep space. By studying the rings of Saturn, we have gained knowledge of much more complex systems such as nebula, spiral galaxies and accretion disks.

This specific case highlights the significance of understanding our local stellar systems, these objects act as astronomical observatories, regions where our ideas and theories can be rigorously tested before our understanding can be applied to more distant objects, or perhaps even the universe at large.

Further Reading

P. Sutton, “Mean Motion Resonances with Nearby Moons: An Unlikley Origin for the Gaps Observed in the Ring Around the Exoplanet J1407b,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 486, pp. 1681-1689, 2019.

M. M. Hedman, P. D. Nicholson, K. H. Baines, B. J. Buratti, C. Sotin, R. N. Clark, R. H. Brown, R. G. French and E. A. Marouf, “The Architecture of the Cassini Division,” The Astronomical Journal, vol. 139, pp. 228-251, 2010.